[ad_1]

Inner Mongolia, 8 a.m.: A measurable fraction of all the computing power on the Bitcoin network is on these shelves.

Inner Mongolia, 8 a.m.: A measurable fraction of all the computing power on the Bitcoin network is on these shelves.

Photo: Stefen Chow

It’s only 8 in the morning when I arrive at my destination in the Ordos prefecture of Inner Mongolia, but already the air is heavy and oppressively hot. My host drives me through a gate, past a sleepy-looking security guard, and into an industrial yard that extends into the dry, barren countryside about as far as I can see.

In front of me are nine warehouses with bright blue roofs, each emblazoned with the logo for Bitmain, a Chinese firm headquartered in Beijing that is arguably the most important company in the Bitcoin industry. Bitmain sells Bitcoin mining rigs—the specialized computers that keep the cryptocurrency running and that produce, or “mine,” new bitcoins for their owners. It also uses its own rigs to stock facilities that it owns or co-owns and operates. Bitmain owns about 20 percent of this one.

Jihan Wu, the CEO of Bitmain, claims that 70 percent of the Bitcoin mining rigs in operation today were made by his company. And, according to a study conducted last winter by the University of Cambridge, in England, it’s likely that most of those machines are plugged into an outlet somewhere in China.

Bitmain acquired this mining facility in Inner Mongolia a couple years ago and has turned it into one of the most powerful money factories on the Bitcoin network. It quite literally metabolizes electricity into money. By my own calculations, the hardware on the grounds—some 21,000 computers—accounted for about 4 percent of all the computing power in the Bitcoin network when I visited.

Like 10-ton paperweights, these machines bear down on the globally distributed ledger of transactions that is Bitcoin, keeping its pages from ever turning backward. Here is where the supply of existing bitcoins is secured. And here is where the banquet of new bitcoins is served.

Speedy Installation: The faster the machines are plugged in, the sooner they can begin gulping down electricity and turning it into money. Racks of bitcoin mining rigs run the length of seven warehouses at Bitmain’s Ordos facility, which is in a constant state of upgrade.

Speedy Installation: The faster the machines are plugged in, the sooner they can begin gulping down electricity and turning it into money. Racks of bitcoin mining rigs run the length of seven warehouses at Bitmain’s Ordos facility, which is in a constant state of upgrade.

Photo: Stefen Chow

The process of mining bitcoins works like a lottery. Bitcoin miners are competing to produce hashes—alphanumeric strings of a fixed length that are calculated from data of an arbitrary length. They’re producing the hashes from a combination of three pieces of data: new blocks of Bitcoin transactions; the last block on the blockchain; and a random number. These are collectively referred to as the “block header” for the current block. Each time miners perform the hash function on the block header with a new random number, they get a new result. To win the lottery, a miner must find a hash that begins with a certain number of zeroes. Just how many zeroes are required is a shifting parameter determined by how much computing power is attached to the Bitcoin network. Every two weeks, on average, the mining software automatically readjusts the number of leading zeros needed—the difficulty level—by looking at how fast new blocks of Bitcoin transactions were added. The algorithm is aiming for a latency of 10 minutes between blocks. When miners boost the computing power on the network, they temporarily increase the rate of block creation. The network senses the change and then ratchets up the difficulty level. When a miner’s computer finds a winning hash, it broadcasts the block header to its next peers in the Bitcoin network, which check it and then propagate it further.

Then two things happen. New transactions are added to the Bitcoin blockchain ledger, and the winning miner is rewarded with newly minted bitcoins. The miner also collects small fees that users voluntarily tack onto their transactions as a way of pushing them to the head of the line. It’s ultimately an exchange of electricity for coins, mediated by a whole lot of computing power. The probability of an individual miner winning the lottery depends entirely on the speed at which that miner can generate new hashes relative to the speed of all other miners combined. In this way, the lottery is more like a raffle, where the more tickets you buy in comparison to everyone else makes it more likely that your name will be pulled out of the hat.

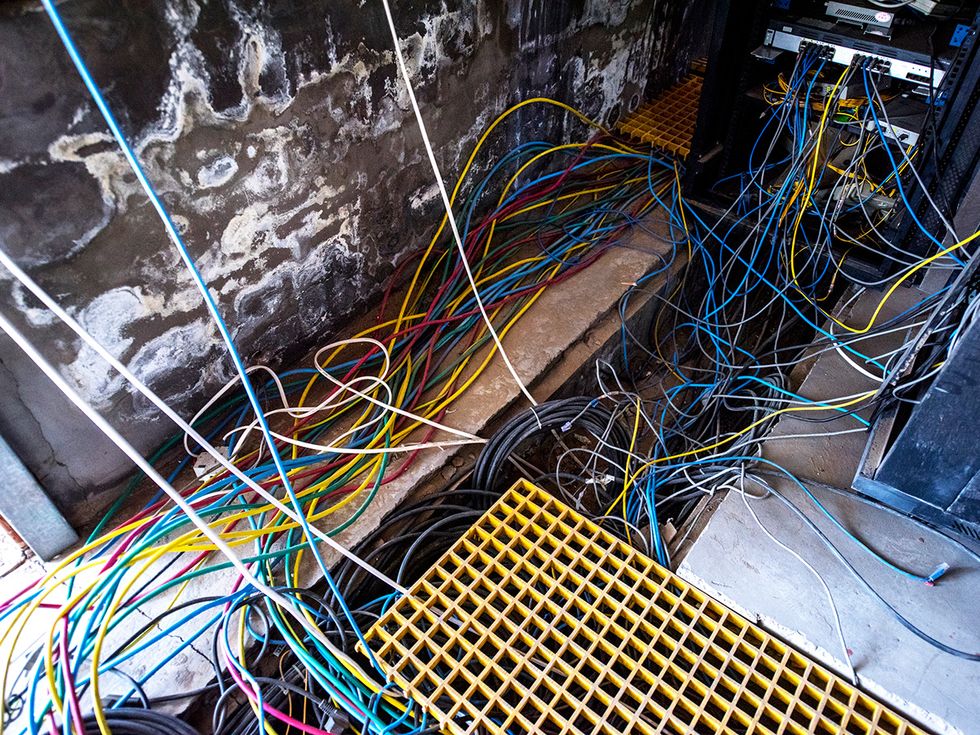

Haste Makes Money: A tangle of networking cables is evidence that the building was constructed and the equipment installed at breakneck speeds.

Haste Makes Money: A tangle of networking cables is evidence that the building was constructed and the equipment installed at breakneck speeds.

Photo: Stefen Chow

These dynamics have resulted in a race among miners to amass the fastest, most energy-efficient chips. And the demand for faster equipment has spawned a new industry devoted entirely to the computational needs of Bitcoin miners. Until late 2013, generic graphics cards and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) were powerful enough to put you in the race. But that same year companies began to sell computer chips, called application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), which are specifically designed for the task of computing the Bitcoin hashing algorithm. Today, ASICs are the standard technology found in every large-scale facility, including the mining farm in Ordos. When Bitmain first started making ASICs in 2013, the field was thick with competitors—BitFury, a multinational ASIC maker; KnCMiner in Stockholm; Butterfly Labs in the United States; Canaan Creative in Beijing; and about 20 other companies spread around China.

Bitmain gained an edge by supplying a superior product in large quantities, a feat that has eluded every other company in the industry. The Ordos facility is stuffed almost exclusively with Bitmain’s best performing rig, the Antminer S9. According to company specs, the S9 is capable of churning out 14 terahashes, or 14 trillion hashes, every second while consuming around 0.1 joules of energy per gigahash for a total of about 1,400 watts (about as much as a microwave oven consumes).

Although BitFury claims to be producing chips whose performance is nearly identical to those used in the S9, the company has packaged them into a very different product. Called the BlockBox, it’s a complete bitcoin-mining data center that BitFury ships to customers in a storage container. Beijing’s Canaan Creative is still selling mining rigs to the public, but it offers only one product, the AvalonMiner 741, and it’s only half as powerful and slightly less efficient than the S9.

Compact Power: At Ordos, Bitmain has installed its most sophisticated mining rigs, Antminer S9s.

Compact Power: At Ordos, Bitmain has installed its most sophisticated mining rigs, Antminer S9s.

Photo: Stefen Chow

An Antminer S9 houses 189 ASICs fabricated by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (the world’s biggest foundry), using its 16-nanometer manufacturing process.

Each ASIC has more than 100 cores, all of which operate independently to run Bitcoin’s SHA-256 hashing algorithm. A control board on the top of the machine coordinates the work, downloading the block header to be hashed and distributing the problem to all the hashing engines, which then report back with solutions and the random numbers they used to get them.

It’s “sort of like an ant colony, where the control board is the queen directing the workers,” says Peter Holm, the director of integrated circuit design at Bitmain, revealing the inspiration for the rig’s name.

All mining ASICs, Bitmain’s included, are performing essentially the same computation—the SHA-256 hashing algorithm—even if they go about it a bit differently. The standard algorithm takes 64 steps to complete, but in Bitcoin it is run twice for each block header, meaning a full round requires 128 steps that are heavy on integer addition. “That’s what dominates the whole design,” says Timo Hanke, the chief cryptographer at String Labs, a cryptography-focused incubator in Palo Alto, Calif. “So, if somebody was to optimize it, they have to optimize the adders. That’s where most of the work is.”

Harsh Conditions: Inner Mongolia has some of the cheapest electricity prices in the world (4 U.S. cents per kilowatt-hour, a government-reduced rate), which is the primary reason miners are setting up shop here. But it comes with a trade-off: The climate outside Bitmain’s warehouses can be brutal, especially in the summer.

Harsh Conditions: Inner Mongolia has some of the cheapest electricity prices in the world (4 U.S. cents per kilowatt-hour, a government-reduced rate), which is the primary reason miners are setting up shop here. But it comes with a trade-off: The climate outside Bitmain’s warehouses can be brutal, especially in the summer.

Photo: Stefen Chow

Despite having similar needs, there is a good deal of diversity in how chip designers build their hashing engines, says Hanke, who also served as the chief technology officer of a now-defunct mining rig manufacturer called CoinTerra. For example, Bitmain uses pipelining—a strategy that links the steps in a process into a chain in which the output of one step is the input of the next. Bitmain competitor BitFury has chosen not to use that technology.

The most pressing problem in the mining chip design is power efficiency, because your return on investment is the difference between how much money you spend on electricity versus how many new bitcoins you can win.

“Here, power is more important than absolute speed. You’re not designing the adders for maximum possible speed, but you’re designing them for the maximum power efficiency,” says Hanke.

If you’re doing your job right, you’re also desperately looking for a way to keep the chips cool. The S9 is meant to operate below 38 °C. A controller on top of the machine samples the ambient temperature and sets the fan speed and the voltage and clock speed of the machine accordingly.

But such measures aren’t enough if you’re mining in a place like Inner Mongolia.

Breathe In: Each warehouse is swathed in netting to keep pollen and dust from getting inside.

Breathe In: Each warehouse is swathed in netting to keep pollen and dust from getting inside.

Photo: Stefen Chow

Inside the warehouse in Ordos, it’s dark, loud, and windy.

A young man named Zhang brings me inside, shouting over a deafening whir. “This is the cool side,” he tells me. All along a wall of the warehouse, the windows have been removed from their frames and replaced with desert fans—panels of twisted, tightly packed metal strips that are being doused with water from a pipe above.

Zhang walks up to a door between two shelves full of mining rigs, and we step through. “This is the hot side,” he tells me. We’re standing in an empty, brightly lit space that serves as the heat dump for the facility. The exhaust fans from all the mining machines on the other side are poking out through little holes in a metal wall, blasting hot air into the space, where it gets purged to the outside by another wall full of giant metal fans.

With the Antminers needing to stay below 38 °C, Mongolia is not the ideal location for a mining facility. It had been above 40 °C for several days when I visited in July. And in the winter, it can fall to –20 °C, cold enough for Bitmain to add insulation to the facilities. Dust is a problem as well, which is why the interior of every warehouse I walk through is veiled in a fine fabric filter.

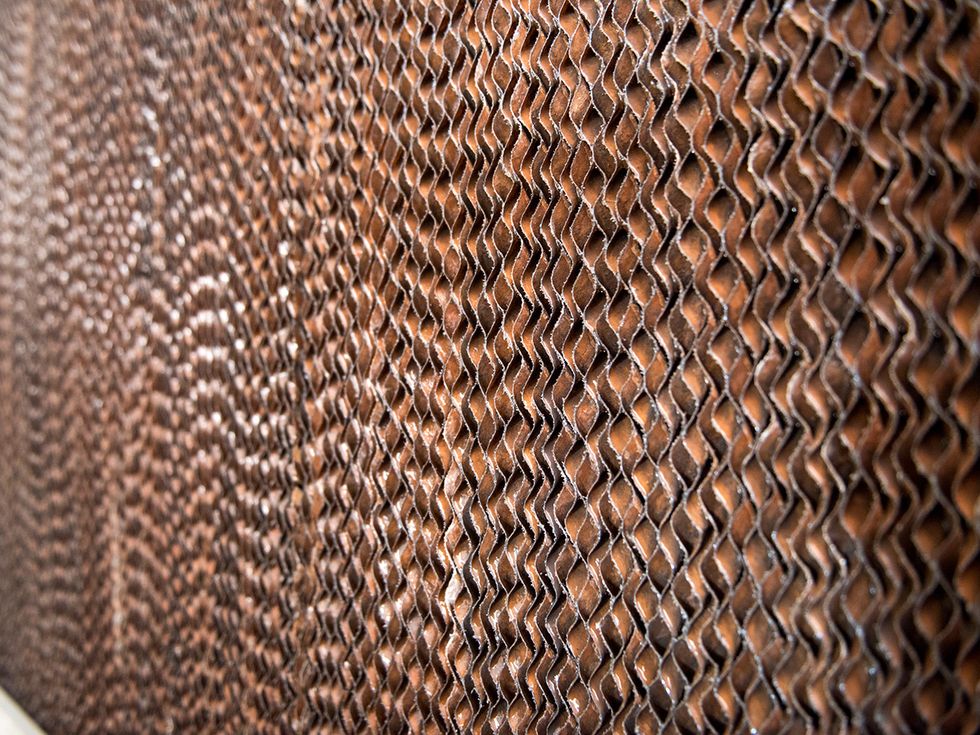

Drip Dry: Windows have been removed from one full side of the warehouse and replaced with desert fans—panels of twisted metal that get doused with water from a pipe running along the top. As air enters the warehouse through these desert fans, the water evaporates and cools the interior.

Drip Dry: Windows have been removed from one full side of the warehouse and replaced with desert fans—panels of twisted metal that get doused with water from a pipe running along the top. As air enters the warehouse through these desert fans, the water evaporates and cools the interior.

Photo: Stefen Chow

To save money on cooling, some mine operators have opted for cooler climates. BitFury also runs three large mining facilities, one of which is in Iceland to benefit from the cool weather. “Many data centers around the world have 30 to 40 percent of electricity costs going to cooling,” explains Valery Vavilov, the CEO of BitFury. “This is not an issue in our Iceland data center.”

The other two BitFury mines are in Tbilisi, in the Republic of Georgia, where the weather is much warmer. According to Vavilov, the company has developed a two-phase immersion cooling technology with their subsidiary, Allied Control. The system bathes the mining machines in a dielectric heat-transfer liquid called Novec, which cools the computers as it evaporates. The system is now deployed at the Georgia data centers.

Heat Pumps: On the hot side of the warehouse, industrial fans blow air back out into the courtyard. Temperatures on this side exceed 40 °C (104 °F).

Heat Pumps: On the hot side of the warehouse, industrial fans blow air back out into the courtyard. Temperatures on this side exceed 40 °C (104 °F).

Photo: Stefen Chow

While heat is definitely an issue for the mining farm in Ordos, the electricity there is dirt cheap, only 4 U.S. cents per kilowatt-hour, with government subsidies. That’s about one-fifth of the average price in the United Kingdom. The only other costs for the facility are the rigs themselves and the salary of the few dozen staff that keeps them operational.

Zhang is part of that staff. He recently graduated from college in Inner Mongolia and started working at the mine only a few months ago. He describes himself as a technician, then points to a man who is standing on a pneumatic lift pulling a mining rig out of the racks. “That’s what I do,” he tells me.

The controller on the S9 has a red light that goes off when it detects a malfunction. Technicians like Zhang are on hand to scan the racks for sick rigs. When they find one, they pull it out and send it to a house on the factory lot where other technicians diagnose the problem, fix it, and get the machine back on the line. Sometimes it’s a failed chip. Other times it’s a burned-out fan. If the problem is more serious, then the rig gets sent all the way to Bitmain’s labs in Shenzhen in southeast China for a proper rebuild. Every moment the rigs spend unplugged, potential revenue slips away.

Given the price of bitcoin at the time I visited Ordos, each individual mining rig at the facility was making around US $10 in bitcoins per day. At that rate, the facility as a whole, which houses over 20,000 Antminer rigs, could bring in $70 million or more per year. And this is just one of the facilities that Bitmain runs.

Heat Shields: The layout of the mining racks is being reconfigured to maintain a cool side and a hot side. The machines are set up on a single rack that traverses the entire length of the warehouse. The fans are aligned to shoot hot air out behind the machines into the hot side of the warehouse, and a barrier is set up to keep the air from circulating back.

Heat Shields: The layout of the mining racks is being reconfigured to maintain a cool side and a hot side. The machines are set up on a single rack that traverses the entire length of the warehouse. The fans are aligned to shoot hot air out behind the machines into the hot side of the warehouse, and a barrier is set up to keep the air from circulating back.

Photo: Stefen Chow

But due to the volatility of bitcoin, it’s impossible to predict the annual revenue of a mining farm. On my flight from China back to the United States, the price of bitcoin crashed 25 percent, from $2,400 to $1,800. In no time at all the operation I visited was bringing in $50,000 less per day. Within a week it was back up, and approaching an all-time high.

Price fluctuations, which have been common in Bitcoin since the day it was created eight years ago, saddle miners with risk and uncertainty. And that burden is shared by chip manufacturers, especially ones like Bitmain, which invest the time and money in a full custom design. According to Nishant Sharma, the international marketing manager at Bitmain, when the price of bitcoin was breaking records this spring, sales of S9 rigs doubled. But again, that is not a trend the company can afford to bet on.

And so, Bitmain has begun to diversify. In addition to Bitcoin businesses, the company has also started to dabble in artificial intelligence and is developing facial-recognition hardware that it plans to sell to the Chinese government.

Competing ASIC maker BitFury has also started seeking profit from nonmining industries. “While we began as just a mining company back in 2011, our company has significantly expanded its reach since then,” says CEO Vavilov. Among other things, BitFury is now providing its immersion cooling technology to high-performance data centers that are not involved in Bitcoin.

Something’s Wrong: Software monitors the operating status of the thousands of mining rigs and alerts workers when one has failed.

Something’s Wrong: Software monitors the operating status of the thousands of mining rigs and alerts workers when one has failed.

Photo: Stefen Chow

For Bitmain CEO Jihan Wu, the of pursuing new revenue streams is a way of protecting the company’s role in Bitcoin, a technology that he describes adoringly. “It’s quite personal that I wanted Bitcoin to be successful,” says Wu. “But as a company we are not allowed to solely rely on the success of Bitcoin. That’s a thing we cannot afford.”

The uncertainty may explain why the giants of the semiconductor industry have thus far shied from entering the fray. But if bitcoin prices remain high, that could change.

“It’s a real testament to Bitmain that they’ve been able to fend off the competition they have fended off. But still, you haven’t seen an Intel and a Nvidia go full hog into this sector, and it would be interesting to see what would happen if they did,” says Garrick Hileman, an economic historian at the London School of Economics who compiled a miner survey with the University of Cambridge.

Home Sweet Repair Shop: One building on the grounds houses a lunchroom, operational center, repair shop, and dormitory. A few dozen employees run the entire facility. Their jobs include scanning the racks for malfunctioning machines, cleaning the cooling fans, fixing broken rigs, and installing upgraded machines. Many of the employees are recent engineering graduates from the local university.

Home Sweet Repair Shop: One building on the grounds houses a lunchroom, operational center, repair shop, and dormitory. A few dozen employees run the entire facility. Their jobs include scanning the racks for malfunctioning machines, cleaning the cooling fans, fixing broken rigs, and installing upgraded machines. Many of the employees are recent engineering graduates from the local university.

Photo: Stefen Chow

What would it take for a competitor to nudge into the fray? For starters, it has to be willing to put a lot of money on the line. Several million dollars can go into chip design before a single prototype is produced. “It takes the willingness to pull the trigger and pay the money,” says Hanke. But he’s confident it will happen. “People will see it’s profitable, and they will jump in.”

Indeed, it may already be happening. This September, GMO Internet Group, a Japanese company with 135 billion yen (US $1.2 billion) in revenues, announced that it was developing its own mining ASIC utilizing 7-nanometer-process technology.

Such disruption would be welcome news to some in the community who argue that Bitmain’s outsized market position in mining hardware is itself a threat to Bitcoin.

This spring, Bitmain caused a minor uproar when a developer found a “backdoor,” called Antbleed, in the firmware of Bitmain’s S9 Antminers. The backdoor could have been used by the company to track the location of its machines and shut them down remotely. While no computer purchaser would find such a vulnerability acceptable, it’s particularly troubling for Bitcoin.

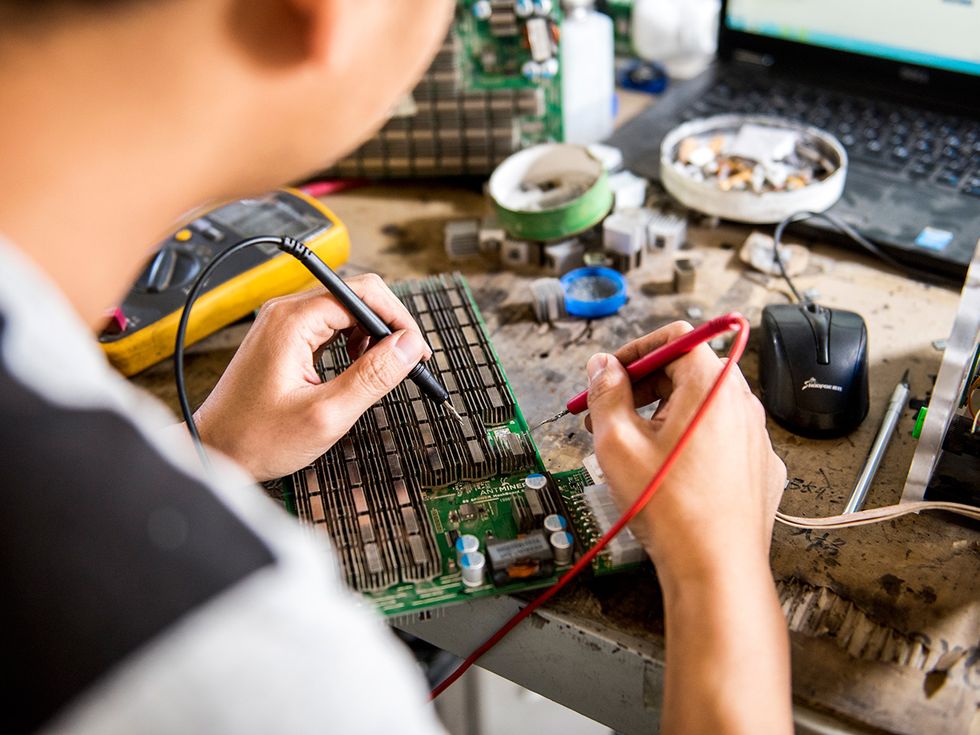

Fix It: In the repair shop, workers manually tend to broken rigs, fixing fans and replacing chips. At each workstation, scavenged jar caps are filled with new ASICs ready to be glued into place. Workers remove heat sinks from circuit boards and replace any failed chips.

Fix It: In the repair shop, workers manually tend to broken rigs, fixing fans and replacing chips. At each workstation, scavenged jar caps are filled with new ASICs ready to be glued into place. Workers remove heat sinks from circuit boards and replace any failed chips.

Photo: Stefen Chow

The Bitcoin protocol was designed to encourage the distribution of hashing power among miners rather than its concentration. The reason? Miners wield power not only over which transactions get added to the Bitcoin blockchain but over the evolution of the Bitcoin software itself. When updates are made to the protocol, it is the miners, largely, who enforce these changes. If the miners band together and choose not to deploy an update from Bitcoin’s core developers, they can stall transactions or even cause the currency to split into competing versions.

A backdoor like Antbleed, if utilized, would give an ASIC manufacturer the power to effectively silence miners who support a version of the Bitcoin protocol that it doesn’t agree with. For instance, Bitmain could have flipped a switch and shut down the entire facility in Ordos if the company found itself in disagreement with the other shareholders.

Wu claims that Antbleed, which has since been patched, was only vestigial code left in by mistake when engineers were trying to build a kill switch for a customer’s own use. There was some skepticism about this explanation, but because the S9’s firmware is open source, users are confident in the patched version. Still, the discovery of it was a startling reminder of the need for diversity in the mining hardware industry.

“Hardware vendors have significant control over Bitcoin,” says Peter Todd, a Bitcoin core developer and applied-cryptography consultant. “A competent backdoor could be extremely difficult to detect and [could] act as a kill switch for hashing power, allowing the network to be killed outright or putting Bitcoin under the control of a single actor.”

Sitting in his Beijing office this July, Wu seemed to think there was enough competition, or at least enough of a threat of competition, to keep Bitmain honest.

“In any specific area, there will be only one player or two. That’s the nature of the ASIC business. If it’s not us, it might be AMD [Advanced Micro Devices]. It might be Nvidia. It might be Intel. It might be someone else,” says Wu. “And if we are doing something wrong, we could be replaced.”

[ad_2]