[ad_1]

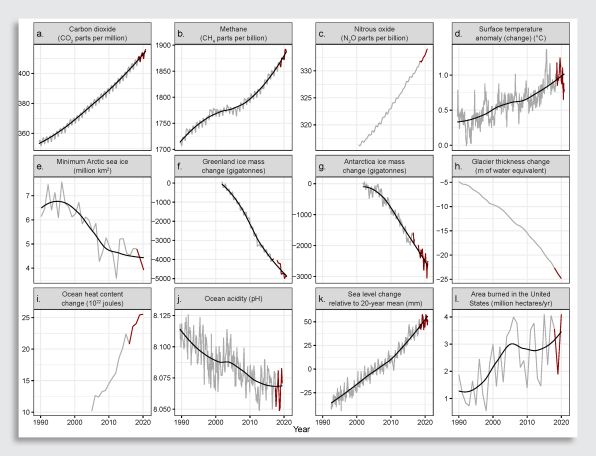

If you were looking for a way to check the planet’s vital signs, you could monitor the coverage of the Amazon rainforest, just like a nurse checks our respiratory rates (they’re the “lungs of the planet,” or at least they used to be). You could check the ocean’s temperature, and even the amount of Arctic sea ice, the amount of livestock, and total CO2 emissions—all stressors that affect the planet’s health, or signs of its health declining.

If you compared those measurements to ones from previous years, and the result you’d get wouldn’t be good: Earth’s vital signs are worsening, many to record levels.

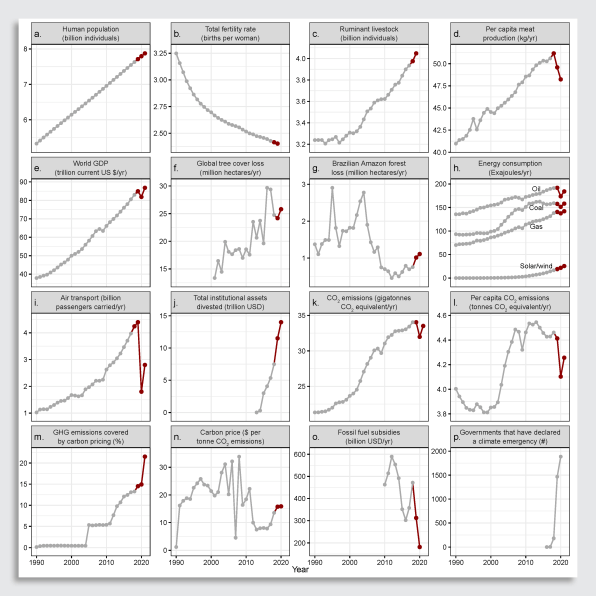

That’s the takeaway from a new study backed by a coalition of nearly 14,000 scientists and led by two researchers at Oregon State University. The study, published in the journal BioScience, tracks 31 indicators of the planet’s health, split into human activities (population, energy consumption, air transport, total emissions, and so on) and the climate’s responses (rising temps, sea ice loss, ocean acidity, and others.).

This report builds on one from 2019 that established the list of vital signs and declared a climate emergency. In the two years since, lead author and Oregon State ecology professor William Ripple says, the climate variables have gotten worse: there’s more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, higher surface temperatures, less Arctic ice, more sea level rise. “One thing that is pretty shocking is the magnitude and number of climate-related disasters that have happened since we published,” he says. “And not only in the last two years, but just in the last two weeks.”

Since that first report, the planet has seen record heat waves, deadly flooding, record drought levels and wildfire seasons—and the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided a natural experiment of how a change in human behavior could affect the planet. The effect of pandemic lockdowns is visible in this latest paper: the number of air transport passengers dropped by 59% in 2020, world GDP and energy consumption slightly dipped—but the climatic responses didn’t really change. “[Lockdowns] did affect the variables somewhat, but it is obvious that was not even close to being enough,” Ripple says.

And all those variables are expected to rebound; including more than a third of the loss in airline passengers projected to be recovered in 2021. “The problem is that we are still in a fossil fuel society,” Ripple says. “We need to have policies to move us away from fossil fuel burning and to alternative sources.” Ending fossil fuel use isn’t the end though. The paper goes on to say we need systemic, transformative changes around our economy, our food systems, and the ways we preserve nature.

Though most of Earth’s vital signs are worsening, there are a few that have improved: the total number of assets divested from the fossil fuel industry has increased to about $14 trillion globally, and government fossil fuel subsidies has fallen to a record low of $181 billion in 2020, a 42% drop from 2019. These are “glimmers of hope,” Ripple says, but there’s also the fact that Brazilian Amazon deforestation is at a 12 year high of 1.11 million hectares destroyed, a troubling find.

When Ripple and 11,000 scientists declared a climate emergency in 2019, they suggested six key steps for action. With more signatories on board now, the nearly 14,000 scientists in support of this paper are repeating the same calls: to eliminate fossil fuels, reduce short-term pollutants like methane and black carbon, restore nature, shift to plant-based diets (world ruminant livestock now number more than 4 billion, more mass than all humans and wild mammals combined) and reduce food waste, transition away from an economy focused on endless GDP growth, and stabilize the population through a focus on girls’ and women’s education and family planning.

This paper adds another three prong approach for policy makers, calling on them to implement a significant carbon price, enact a global phase out (and eventual ban) of fossil fuels, and develop strategic climate reserves to protect and restore nature for both carbon sinks and biodiversity.

“We must address this climate crisis right away,” Ripple says. “We’re going to have, as we’re witnessing, significant human suffering, but if we make the big changes soon, we can limit that suffering. We want to give an update with these vital signs, but we also want to emphasize the importance of moving fast at this point, and thinking big.”

[ad_2]