[ad_1]

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

The final piece of evidence documenting the pandemic-driven “missing generation” of college students was released today: a sharp rise in the number of students failing to return to college.

“We can now add increased attrition of 2019 freshmen to the severe impacts of the pandemic,” said Doug Shapiro, executive director of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

The independent Clearinghouse collects the nation’s most authoritative college-going data. By matching high school graduation records against college enrollment records, the Clearinghouse determines which high school graduates enroll in college, which “persist” through the college years, and which end up earning degrees.

The data released today shows that of the 2.6 million students who entered college as first-time freshmen in the fall of 2019, 74 percent returned for their second year — an unprecedented two percentage point drop, the lowest level since 2012.

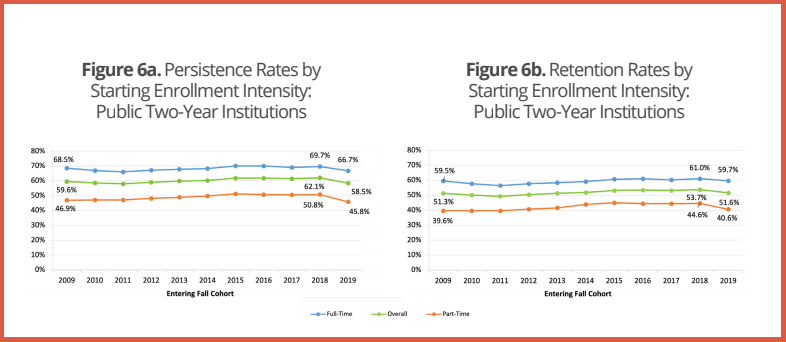

Not surprisingly, community colleges showed the steepest decline in persistence rates, down 3.5 percentage points to 58.5 percent. Community colleges attract a disproportionate number of low-income and minority students, and they have seen the most dramatic enrollment and persistence drops.

Persistence and retention rates fell greatest for part-time students in two-year community colleges. (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center)

In most cases, the explanations are straightforward: These students needed to get jobs — even low-skill, low-paying jobs — to support their families. In theory, these students could return to college now that the pandemic has eased, but there’s little evidence in enrollment trends to suggest this is happening.

Instead, they appear to be forming a missing generation of college students, an unprecedented phenomenon likely to affect the nation’s productivity rate for years. Any country’s international competitiveness is forecast by the skills acquired by young people entering the workforce.

Before today’s data release, there was ample evidence to suggest a missing generation was taking shape. This spring, overall college enrollment fell by 603,000 students, from 17.5 million to 16.9 million — a drop that is seven times worse than the year before when the pandemic first hit and marks the sharpest year-over-year decline since 2011, the first year the Clearinghouse began keeping track.

While the pandemic was expected to eat away at college enrollment, many experts were surprised that a quick recovery in college-going never materialized. Today’s data from the Clearinghouse only makes that news grimmer.

“These losses erase recent improvements that colleges have made in keeping learners on track early,” said Shapiro. “They will ripple through higher education for years.”

[ad_2]