[ad_1]

On the shores of Seneca Lake in upstate New York, a private equity company has bought a decommissioned coal power plant and converted it to burn natural gas. It then switched it back on to become what it describes as a “power plant-cryptocurrency mining hybrid”.

Greenidge Generation Holdings, the company behind the plant, plans to go public later this year, saying it expects to become “the only US publicly listed bitcoin mining operation with its own power source”.

In a presentation to investors, it says its direct line in to the Empire Pipeline system for gas allows it to produce coins for just $3,000 a pop — a hefty margin considering that even after a heavy recent drop on a possible crackdown from Chinese regulators, they sell for about $40,000.

The company says it is proud of shifting away from coal. It is looking to buy more power plants and vastly scale up operations. Climate activists, however, are aghast that fossil fuels will be burnt to mine crypto, and are pushing regulators to clamp down on this and other similar projects to prevent a surge in greenhouse gas emissions.

But no activist has so far had such a profound impact on awareness of bitcoin’s carbon question as Elon Musk, the Tesla chief executive so fond of bitcoin that he loaded up his corporate coffers with $1.5bn of the cryptocurrency.

Musk said last week he had changed his mind, and reversed plans outlined in February to accept bitcoin for payments for his vehicles. “Cryptocurrency is a good idea on many levels and we believe it has a promising future, but this cannot come at great cost to the environment,” he said.

The statement generated a backlash from bitcoin believers, some of whom have made huge returns from early bets on the asset class and see it as the future of money. Crypto proponents have accused him of ignorance over mining methods or of seeking to protect the shadowy interests of big government. A new crypto coin named “FuckElon” has appeared.

To academics who for years have been measuring bitcoin’s energy intensity, however, Musk has simply pointed out an established truth, albeit in his eccentric manner. It is a question so far largely ignored by governments, by heavy-hitting environmental charities, and by the banks and exchanges that facilitate the vast cryptocurrency industry.

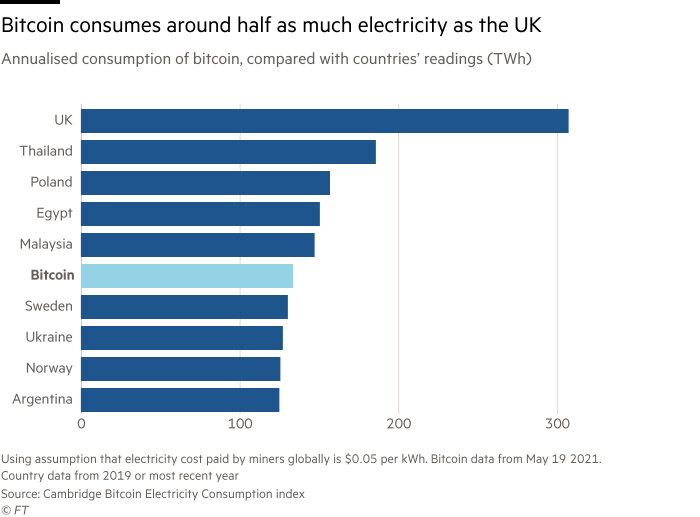

“Bitcoin alone consumes as much electricity as a medium-sized European country,” says Professor Brian Lucey at Trinity College Dublin. “This is a stunning amount of electricity. It’s a dirty business. It’s a dirty currency.”

Economic authorities are starting to take notice. The European Central Bank on Wednesday described cryptoassets’ “exorbitant carbon footprint” as “grounds for concern”. In a paper earlier this month, Italy’s central bank said the eurozone’s payments system, Tips, had a carbon footprint 40,000 times smaller than that of bitcoin in 2019.

Measuring precisely how dirty bitcoin is has become a cottage industry in itself. The latest calculation from Cambridge university’s Bitcoin Electricity Consumption index suggests that bitcoin mining consumes 133.68 terawatt hours a year of electricity — a best-guess tally that has risen consistently for the past five years. That places it just above Sweden, at 131.8TWh of electricity usage in 2020, and just below Malaysia, at 147.21TWh.

The true figure for bitcoin could in fact be much higher; Cambridge’s extreme worst-case scenario calculation, based on miners using the least energy-efficient computers on the market as long as the process is still profitable, has peeled away from its central estimate sharply since November last year as the price of bitcoin has rocketed. The rationale: a rising bitcoin price attracts new miners, and also means that mining with older, less efficient equipment, makes financial sense.

The higher price also means the machines producing bitcoin are forced to complete ever-tougher puzzles in search of their quarry. At the upper limit, bitcoin’s electricity consumption would be about 500TWh a year. The UK consumes 300TWh. About 65 per cent of the crypto mining comes from China, where coal makes up around 60 per cent of the energy mix.

Naturally, there is space for disagreement on these statistics, and all studies on the issue accept elements of uncertainty. “There’s a lot of shades of grey,” says Michel Rauchs, a research affiliate who works on the Cambridge index.

Rauchs points out that a slice of the mining in China comes from clean hydroelectric power, including with machines that are transported from the north to the south of the country on trucks each year in the wet season. That hydro power is not necessarily diverted from anywhere else; some of these power stations were founded for factories that no longer exist, Rauchs says. In those cases, “I don’t see that it’s necessarily a problem”, he adds. About 75 per cent of miners use some kind of renewable energy, Cambridge studies show, but renewables still account for less than 40 per cent of the total energy used. Some mining may also be conducted off-grid, making it harder to track.

All this nuance makes a difference. Still, the possibility of global official intervention to cut the industry’s energy consumption is an “existential threat”, says Rauchs.

Machines on overdrive

Energy consumption on some scale is a feature, not a bug, of bitcoin — a digital currency launched by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto 12 years ago. Its detachment from the global financial and governmental system — still the most alluring feature for users seeking anonymity or wishing to bypass central banks — means it needs a new way to establish trust and security.

It does this by awarding miners coins in return for intensive puzzle-solving on the blockchain, making it a so-called “proof of work” coin. The puzzles are sufficiently hard to prevent hackers and other nefarious actors from taking control of the network, and the faster that miners can submit random numbers into the bitcoin algorithm, the more likely they are to unlock the coins. This all demands powerful machines running at full tilt.

Luckily for bitcoin miners with access to cheap energy and efficient machines, it is usually worth it. The price of bitcoin has dropped by about $30,000 apiece since the peak last month, but it has climbed by more than 200 per cent since late 2020 and more than 1,000 per cent since 2019.

Bitcoin is not the only energy-intensive cryptocurrency, but it is by far the biggest. Others include litecoin, ether and the light-hearted but rapidly growing dogecoin — initially an internet joke based on a Shiba Inu dog.

A March 2020 study by energy research journal Joule said bitcoin accounted for about 80 per cent of the market capitalisation of “proof of work” coins, of which an estimated 500 exist, and about two-thirds of the energy. “Understudied currencies add nearly 50 per cent on top of bitcoin’s energy hunger, which already alone may cause considerable environmental damage,” the study claimed.

Some cryptocurrencies are seeking to shift to a less energy-intensive “proof of stake” model, where a system allocates coins to verifiers, akin to miners, who put up coins for collateral. In the event of fraud, verifiers stand to lose their stakes, establishing trust through this channel rather than through energy-intensive “work”. Ether, the cryptocurrency native to the ethereum blockchain network, has been working on a shift to this model for more than two years, but the project is dogged by technical difficulties. Musk has also dangled the possibility that he could back other coins with a lighter energy impact.

A greener version of bitcoin is, in theory, possible. Bitcoin’s code could switch to a less energy-intensive consensus mechanism, whereby a new section of the blockchain ledger underlying the cryptocurrency would follow different rules. However, every miner would need to switch for the new path to work. Industry insiders say it is hard to imagine the entire bitcoin community, which is peppered with disagreements, lending support to such a plan.

Other ideas, such as labelling individual bitcoins as clean or dirty depending on the energy used to mine them, would also be hard to verify, and create a two-tier bitcoin system that was likely to lack support.

“Bitcoin could be the first inefficient version of a disruptive technology,” says Dr Larisa Yarovaya, a lecturer at Southampton university. “It should die for the common good of the planet and be replaced by a new model. It consumes more electricity than a country. All the rest is detail.”

Yarovaya, a former Russian Paralympic swimmer, frequently fields criticisms of her analysis and motivations from bitcoin proponents. She is undeterred, however. “It’s common sense,” she says. “[The energy consumption] is not justifiable by the high price of bitcoin. It is a speculative asset. It does not create a substantial amount of employment. It’s not widely used for transactions.”

Such concerns have not, however, sparked high-profile campaigning from environmental groups. Friends of the Earth, an advocacy group, says it is still getting to grips with the issue, as is Greenpeace, whose US arm started accepting bitcoin donations in 2014. After inquiries from the Financial Times, Greenpeace says it will now scrap the facility, which has not been heavily used. “As the amount of energy needed to run bitcoin became clearer, this policy became no longer tenable,” says Greenpeace.

Validation concerns

Environmental concerns have also not deterred a clutch of investment banks from entering the sector, despite their public commitments to sustainable development goals: Citigroup said recently it was exploring what role it could play in crypto services; Goldman Sachs has reopened bitcoin derivatives trading; and Morgan Stanley plans to offer clients access to bitcoin funds. None of these banks wished to comment on the issue of energy consumption.

Yarovaya says public companies dabbling in cryptocurrencies have served to “validate” the asset class, pumping up prices and in turn indirectly cranking up the energy usage. “They need to explain themselves,” she says, adding that cryptocurrency buyers should also take individual responsibility for their contribution.

Nigel Topping, who was appointed by the UK government to co-ordinate with businesses over climate goals ahead of the COP26 talks later this year, says bitcoin is not likely to be on the agenda for climate discussions among governments in Glasgow, but it is starting to become a real issue in broader policy discussions. “It’s becoming one of the climate baddies,” he says. “People who care about climate are in a bit of dismay. It’s just a silly idea. Proof of work is proof of burning [fossil fuels]. It’s working directly against what we’re trying to do.”

The UN is also looking at ways it can prevent the growth of cryptocurrencies from undermining its work on climate change, and is supporting the “Crypto Climate Accord” initiative, led by the Rocky Mountain Institute, says Topping. The group is not aiming to slow innovation in digital finance, but wants to ensure that future blockchain-based projects are designed to consume less energy.

Max Boonen, a former banker and founder of cryptocurrency trading platform B2C2, says “there’s a cost” to the environment from this industry, some of which is balanced out by the benefits of bitcoin’s “censorship resistance”.

Do crypto market participants worry about the energy usage? “Not in the slightest,” says Boonen. “Anyone in this market feels comfortable enough about the environmental costs. If you think it’s a problem, you don’t participate.” Nonetheless Boonen says he considers himself to be an environmentalist. He offsets some of the carbon involved in his work through “effective altruism”, such as donations to charities.

Bitcoin proponents remain convinced that the benefits outweigh the costs, arguing that cryptocurrencies provide the basis for the financial system of the future. Some, such as Jack Dorsey’s Square and Cathie Wood’s Ark Investment, argued in a white paper that the bitcoin network could in fact incentivise the more rapid development of renewable energy. “Increasing bitcoin mining capacity could allow the energy provider to ‘overbuild’ solar without wasting energy,” the paper said.

Banks and asset managers keen to meet client demand for crypto services are looking at carbon offsets. Much heavier reliance on renewable energy would soften the blow, but would still draw criticism by diverting clean power from other parts of society. After protests by residents and green NGOs, the Greenidge project in New York state announced plans to make its bitcoin generation carbon neutral by buying carbon credits. The company says it is “committed to exploring and investing in renewable energy initiatives across the country”.

Mandy DeRoche, an attorney at Earthjustice, which is campaigning against this and other resurrections of what she calls “zombie” fossil fuel-based power plants, says Greenidge buying credits is “irrelevant” considering the amount of greenhouse gases emitted, and the time has come for a more serious look at potential regulation.

“People can get distracted by, like, ‘what is bitcoin and what does it do?’ Honestly I don’t care what bitcoin does. I care that it is hugely energy-intensive, and that there are maybe better ways to go about bitcoin mining than this very inefficient, very energy-intensive process,” she says.

Additional reporting by Ændrew Rininsland and Joanna S Kao

[ad_2]