[ad_1]

Here’s a sobering statistic: Last year, more than half the states in the U.S. — including New Hampshire — experienced more deaths than births.

“That’s never happened in American history,” says Kenneth Johnson, senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire. “Nothing close has ever happened.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a big part of what’s going on.

According to new data released by the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a record 3,376,000 deaths were recorded in the U.S. last year, 18% more than in 2019. At the same time, births dropped by 4% to 3,605,000 in 2020.

And that, Johnson said, coupled with lower immigration, meant the U.S. saw its smallest annual percentage gain in population in at least 100 years.

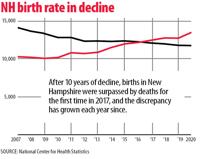

New Hampshire has had more deaths than births every year since 2017.

The NCHS data shows that New Hampshire recorded 11,773 births and 13,511 deaths in 2020. That represented a less than 1% drop in births from the previous year, but a 6% increase in deaths.

Last year, near the start of the crisis, Johnson predicted that birth rates would drop as families postponed pregnancy during such uncertain, scary times. He proved to be correct.

In December, he said, “Nine months after the pandemic began to be a significant concern, the births dropped almost 8% in the United States,” compared with December 2019.

Full figures aren’t in for January yet, but preliminary data show the number of births dropped 9% to 10% from the year before, he said.

Birth rates already had been dropping in New Hampshire and across New England, Johnson said. “Then COVID hits and the birth rates drop again,” Johnson said.

Many people lost jobs or were working on the front lines during the crisis, he said.

“We were already seeing these low numbers of births, and this was just one more factor that would give people pause to think about whether it was a good time to have a baby,” he said.

Kenneth Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire

Birth rates have been dropping most sharply among women in their 20s, going back to the great recession, Johnson said. “They’re the ones who could say, ‘We’re waiting,’” he said.

But many of those women are now in their 30s and may have been ready to start families when the pandemic hit and postponed those plans.

“The long-term question is: Are these going to be delayed babies or are they just not going to come at all?” Johnson said.

Nationwide, Johnson said, the increase in deaths was not just related to the number of people who died from COVID.

Scientists also look at “excess deaths,” the number of people who died because they didn’t seek medical care in time, for example for chest pain, or who put off diagnostic testing because of the crisis.

The implications of these demographic trends, Johnson said, “ripple all the way up through the system.”

Hospitals are closing maternity wards as birth rates drop. School systems may have to reduce classes, lay off staff or merge with neighboring districts if they don’t have enough students.

“The universities have to be concerned, and then eventually it’s going to get to the labor force,” he said.

In a state like New Hampshire, with an older population, those ripples will continue to spread, he said.

“Who’s going to be the volunteer firefighters? Who’s going to be the people who do all those jobs in the communities, like coach the team, be on the planning board, run the PTA, help with the church? All the things that make communities go.

“Eventually this could be problematic for them.”

New Hampshire does have one advantage: It gains domestic migration every year, and many of those new residents tend to be in their 30s and 40s, Johnson said.

It remains to be seen how long the effects of COVID will linger, Johnson said.

“We know there already have been a lot of COVID deaths this year, so COVID’s still going to be a factor in the mortality patterns this year. By 2022, will that be over? Or is it going to be an ongoing thing?”

On the other side of the scale, “Are the women who delayed these babies going to have some of them?” he asked.

“It’s a big story and we don’t know the end of it,” Johnson said.

The pandemic has changed so much about our lives, and many people have been doing a lot of soul-searching, he said. It’s possible that could lead to a baby boomlet in the future.

“I think a lot of people have taken a serious look at themselves and their lives.” he said.

“People may think differently about things, having gone through this, about what is important to them.”

[ad_2]